Australia’s favourite cryptid

by Murray Byfield

Thylacine (The Tasmanian Tiger)

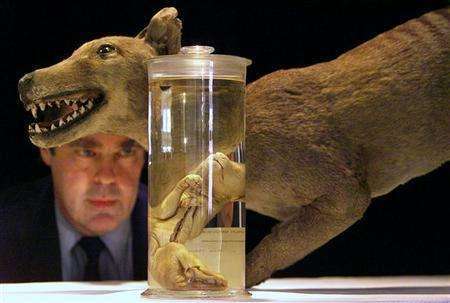

The Thylacine would have to be Australia’s most recognizable Cryptid next to the Yowie. There is no debate about whether the Tasmanian Tiger existed or not, only if the Tiger still exists today. The last captive Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus, meaning pouched dog with wolfs head) died in captivity at Hobart Zoo on September 7th, 1936. The scientific community believed that this was the last Tiger in existence and the species was officially declared extinct in 1986. Tasmanian Tigers lived on the Australian mainland up until approximately 3000 years ago they were most likely killed off by the arrival of the Dingo (Canis lupus dingo).

Its habitat was eucalypt forest, wetland and grasslands and was not only specific to mainland Australia and Tasmania but also New Guinea. The Tassie tiger was a carnivorous marsupial whose pouch actually faced backwards unlike most marsupials to prevents sticks and other foreign objects entering its protective pouch. S/he was 1.8m long including the tail, stood 58cm tall and weighed about 30 kg. Its coat was tan-light brown with a series of black stripes from the tail to the shoulders. The Thylacines tail didn’t wag like regular dogs and wolves but was purely functional for balance like other marsupials such as the Kangaroo and Wallaby. Its skull was quite large and unlike placental carnivores could open up to 120 degrees.

It hunted at night in open woodland and heath and then returned its home in the day which it made in hollow tree trunks and small caves. It was quite often seen in small groups that suggest it was not territorial although its home range was between 40-80km. He was a shy creature who sometimes became inquisitive.

Many people blame the appearance of white Australians for the disappearance of the Tasmanian Tiger as the Tiger was very partial to livestock especially sheep. Many were shot by farmers protecting their herds, even a bounty of £1 for each dead specimen was placed on the Tiger. 2184 bounties were paid, it became a protected species in 1936 but by then it was too late.

But evidence has come to light that it was probably a number of factors that led to its apparent extinction. As on the mainland the introduction of the canine (Canis lupus dingo) led to reduced numbers. But more specifically a contagious disease was also responsible for the demise of this wonderful creature. A disease very similar to which the Tasmanian Devil is currently suffering from.

A cloning project was undertaken a few years back to bring the Tassie Tiger back from extinction. Using DNA collected from a Thylacine pup preserved by the Australian Museum and splicing it was canine DNA. The project was subsequently abandoned 15th February 2005 due to lack of viable genetic material and presumably cost.

The Thylacine physically speaking was very similar to a regular canine apart from it being a marsupial it most have evolved under the same conditions as wolves and other canids. Looking at a Tiger you can see the similarities to other marsupials such as the kangaroo and wallaby i.e. The thick tail flattened hind legs which apparently it would at times stand up on like a Kangaroo. Although the Tasmanian Devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) is probably its closest living relation.

Does the Tassie tiger still exist? Many people think so and many are hopeful. Every now and then a picture of a Thylacine shows up and are not very convincing. Several expeditions have been carried out to find evidence of the Tigers survival. See list below:

1937 – Sergeant Summers leads a search in the north-west of the state, recording many recent sightings by other persons in a large area between the Arthur and Pieman Rivers, although the party itself did not see any thylacines. He recommends a sanctuary in that area.

1945 – Well-known naturalist David Fleay searches the Jane River to Lake St Clair area, finding possible thylacine footprints.

1959 – Eric Guiler leads a search in the far north-west, an area which produced many bounties and finds what appeared to be thylacine footprints.

1963 – Eric Guiler leads a search in the Sandy Cape area but finds no evidence.

1968 – Jeremy Griffiths, James Malley and Bob Brown embark on a major search. Although they collect reports of sightings, they find no evidence of the thylacine.

1980 – Parks and Wildlife Officers, Steven Smith and Adrian Pyrke, search a wide area of the State using three automatic cameras. No evidence of thylacines is found.

1982-83 – Parks and Wildlife Officer, Nick Mooney, undertakes an extensive but unsuccessful search to confirm the 1982 sighting reported by Hans Naarding near the Arthur River in the State’s north-west.

1984 – A search in Tasmania’s highlands by Tasmanian Wildlife Park owner, Peter Wright, fails to turn up conclusive evidence.

1988-93 – Separate photographic searches by wildlife photographer, Dave Watts and Ned Terry fail to record a thylacine.

Apart from the lack of physical evidence sightings continue from Tasmania to New Guinea. See list below:

The Australian Rare Fauna Research Association reports having 3,800 sightings on file from mainland Australia since the 1936 extinction date.

Mystery Animal Research Centre of Australia recorded 138 up to 1998.

Department of Conservation and Land Management recorded 65 over the same period.

Independent Thylacine researchers Buck and Joan Emburg of Tasmania report 360 Tasmanian and 269 mainland post-extinction 20th century sightings.

Figures compiled from a number of sources.

On the mainland, sightings are most frequently reported in Southern Victoria.